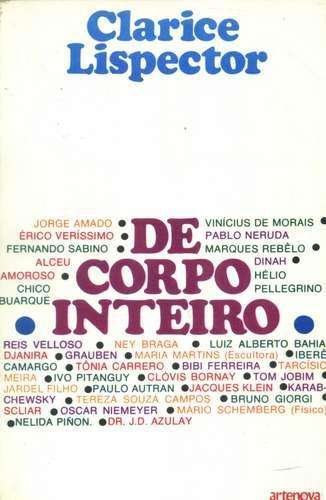

De Corpo Inteiro Clarice Lispector Pdf

Passionate FictionsThis page intentionally left blankPassionate Fiction:Gender, Narrative, and Violence in Clarice Lispector Marta PeixotoUniversity of Minnesota Press 3MinneapolisLondonCopyright 1994 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota Chapter 2, 'Female Power in Family Ties,' first appeared as 'Family Ties: Female Development in Clarice Lispector,' in The Voyage In: Fictions of Female Development, edited by Elizabeth Abel, Marianne Hirsch, and Elizabeth Langland, copyright 1983 by the Trustees of Dartmouth College, reprinted by permission of the University Press of New England. Chapter 5, 'Rape and Textual Violence,' first appeared as 'Rape and Textual Violence in Clarice Lispector,' in Rape and Representation, edited by Lynn Higgins and Brenda Silver, copyright 1991 by Columbia University Press, New York, reprinted by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press 2037 University Avenue Southeast, Minneapolis, MN Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Peixoto, Marta. Passionate fictions: gender, narrative, and violence in Clarice Lispector / Marta Peixoto. Includes bibliographical references (p. ISBN 0-8166-2158-6 (acid-free). ISBN 0-8166-2159-4 (pb.: acid -free) 1.

Lispector, Clarice—Criticism and interpretation. Women in literature. Sex role in literature. Violence in literature.

Title PQ9697.L5 869.3-dc20The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.93-29690 CIPFor Jim, Daniel, Thomas, and MarianaThis page intentionally left blankContentsAcknowledgments ix Introduction xi 1. The Young Artist and the Snares of Gender 1 2. Female Power in Family Ties 24 3. The Nurturing Text in Helene Cixous and Clarice Lispector 4. A Woman Writing: Fiction and Autobiography in The Stream of Life and The Stations of the Body 60 5.

Rape and Textual Violence 82 Afterword: The Violence of a Heart 100 Notes 103 Bibliography 109 Index 113vii39This page intentionally left blankAcknowledgmentsOver the many years it has taken me to write this book I have profited in ways I cannot even measure from conversations with students and colleagues here and in Brazil, and from the responses of audiences to the lectures I have given on Lispector. I am also very grateful for the institutional support I have received in the form of several grants and fellowships from Yale University (a Whitney Griswold Faculty Research Grant, a summer travel grant from the Yale Center for International and Area Studies, and a Senior Faculty Fellowship) and a sabbatical leave from New York University. I would also like to thank the staff at the ArquivoMuseu de Literatura at the Fundagao Casa de Rui Barbosa in Rio de Janeiro, especially Eliane Vasconcellos, who allowed me to look at materials she was still engaged in cataloguing for the Clarice Lispector Archive. Two sections of this book were published previously in somewhat different forms. Chapter 2 appeared in The Voyage In: Fictions of Female Development, edited by Elizabeth Abel, Marianne Hirsch, and Elizabeth Langland.

A version of chapter 5 appeared first in the proceedings of a conference at the University of Texas at Austin, Transformations of Literary Language in Latin American Literature, edited by K. David Jackson. Later, another version was published in Rape and Representation, edited by Lynn Higgins and Brenda Silver. I thank the editors for their invitations and helpful comments. Participation in those projects first made me see that there would be an audience for a book of this kind in English.

Many friends and colleagues have provided invaluable comments on drafts of this book over the years. My greatest debt is to my husband, Jim Irby, always my ixxACKNOWLEDGMENTSfirst reader, for his numerous and patient readings of the manuscript in its many versions, for his attention to details, his insistence on precision and clarity, and his many helpful suggestions. Marianne Hirsch also read the entire manuscript, some sections in more than one draft.

I thank her for her generosity, her many thoughtful comments, and, not least, her contagious enthusiasm for intellectual projects. (For other projects, too.) Sylvia Molloy has been a most supportive friend and critic throughout the writing of this book; her insightful reading of the manuscript clarified some of its latent articulations, allowing me in turn to sharpen them in the final version. Elizabeth Abel provided unfailing friendship and brought to sections of the book pertinent questions and a keen editorial eye.

I would also like to thank the anonymous readers for their thought-provokin comments; I hope that my attempts to respond to their objections have improved the book. Although many friends offered me their help during the writing of this book, when family and professional urgencies clashed more than once, I owe special thanks to Jane Coppock, whose presence and cheerfulness were enormously heartening to me and my children. And finally, although my sons, Daniel and Thomas, have not exactly helped with this project, I am grateful to them nonetheless for keeping me busy and happy with challenges of another sort.IntroductionCuando a la casa del lenguaje se le vuela el tejado y las palabras no guarecen, yo hablo.

When the house of language has its roof blown off and words do not shelter, I speak. Alejandra Pizarnik, 'Fragmentos para dominar el silencio' (Fragments to overcome silence) IClarice Lispector might, but for a twist of fate, have become a writer in the English language. She was born in the small Ukrainian village of Tchetchelnik: a necessary stop for her birth along the way when her parents, Ukrainian Jews, had set out to emigrate, not yet knowing their destination. They had relatives both in the United States and in Brazil and for a while hesitated between North and South America (Moreira 1981).1 Arriving in Brazil at age two months, Lispector came to consider the country and its language her own. Like other major Brazilian Writers, Lispector looked upon the Portuguese language with some melancholy, witnessing the meager audience it could afford her: o tumulo do pensamento, 'the tomb of one's thought,' she called it in one essay where she measures the advantages and disadvantages of writing in Portuguese (DW 134).

At the time of xixiiNTRODUCTIONLispector's death in 1977, only three of her books had been translated into French or English. How astonished she would be to witness the recent upsurge of translations of her work: most of her fourteen books of fiction are now available in English, French, and Spanish, and several have been translated into other languages. For Lispector, writing in Portuguese offered a challenge that she describes in the same essay: It's not easy.

It's not malleable. And, since thought has not worked upon it profoundly, it tends to lack subtleties, and to kick back at those who boldly dare to transform it into a language of feeling and alertness. The Portuguese language offers a real challenge to any writer. Especially to those who write removing from things and people the first layer of superficiality.

Sometimes it reacts when confronted by a more complicated process of thought. Sometimes it takes fright at the unexpectedness of a phrase.

I love to handle it—as I loved to ride a horse and guide it with the reins, sometimes slowly, sometimes at a gallop. (DW 134) Lispector's mode of writing would have required a struggle with any language, just as it did with established literary genres, especially in her later work. Since publication of her first book, Perto do coragao selvagem (1944; Near to the Wild Heart), critics have recognized a distinctive contribution in Lispector's original, often strange language, dense with paradoxes, unusual phrases, and abstract formulations that tease and elude the rational intelligence. Joao Guimaraes Rosa, an acknowledged master of twentieth-century Brazilian fiction and a Joycean innovator in language himself, told an interviewer that 'every time he read one of her novels he learned many new words and rediscovered new uses for the ones he already knew' (Rodriguez Monegal 1966, 1001). The second lesson Rosa derived is perhaps more to the point: Lispector's linguistic inventiveness centers not so much on the lexical level, on the use of unusual words or neologisms (in which Rosa himself excelled), but rather on syntactical contortions and strange juxtapositions, creating semantic pressures that unsettle the meaning of words and concepts. Although Lispector preferred to think of herself as a writer unmodified by the adjective 'female,'2 issues of gender are crucial in her work. This book, which takes as its intellectual and theoretical ground recent feminist critical approaches, studies the pressures Lispector brings to bear on the fixities of gender and the routines of narrative, pressures similar to those that agitate her language.

My project is to study the nexus between gender, narrative, and violence, an aspect of Lispector's work that has not been sufficiently recognized, even by her feminist critics. The female dimension of Lispector's writing has been discussed by many critics. Helene Cixous finds in her texts a feminine libidinal economy, revealing it-INTRODUCTIONxiiiself in openness and generosity, or gentle, identificatory movements toward objects and beings, an interpretation I question in chapter 3. Other critics find a feminist parti pris in Lispector's fiction, and read in various of her texts a critique of social and narrative structures that confine women. Although I do not disagree with this position, I attempt to include her defense of women and the feminine in a more encompassing perspective, charting what I see as a conflictive course in Lispector's texts, where a feminist happy ending seldom occurs.

Lispector and her female protagonists engage in work that Teresa de Lauretis identifies as necessary for women as producers of meaning: 'a continued and sustained work with and against narrative, in order to represent not just the power of female desire but its duplicity and ambivalence. The real task is to enact the contradictions of female desire and of women as social subjects, in terms of narrative' (de Lauretis 1984, 156). It is in the texts with a metaflctional dimension, where the protagonist is a self-reflexive writer, that I find the best examples of Lispector's fierce struggle with gender and narrative, which produces a formal and thematic violence. Challenging limits and courting excess, Lispector invokes a Dionysian force in her attempt to question and disrupt the fixity of gender, of established genres and narrative forms, and to authorize a writing that not only represents women, but also often claims to be itself moved by powers especially accessible to women. 'I feel in me a subterranean violence, a violence that only surfaces in the act of writing,' affirms the female writer-protagonist of Lispector's posthumous novel Um sopro de vida (1978; A Breath of Life, 53).

In the texts I choose for analysis, I find many manifestations of violence articulated with gender and narrative. There is, first, a mimetic violence: the representation of dominating or aggressive interactions between men and women, often set in the family or placed within larger systems of social and even racial oppression. In her refusal to see women simply as innocent victims, Lispector runs counter to a major tendency in feminist thought that Jessica Benjamin also opposes: the construction of 'the problem of domination as a drama of female vulnerability victimized by male aggression' (Benjamin 1988, 9).

Lispector observes not only the sufferings of women under patriarchy, but also their sometimes devious access to an aggressive power; in larger terms, she writes about the multiple violences unavoidably present in biologic, psychic, and social life. Lispector's texts also exemplify and at times metafictionally discuss what we might call a narrative violence.

In her writing of the 1970s, the struggle with narrative that Lispector's work foregrounds includes a conflictive juxtaposition of genres: she uses autobiography to call into question the supposed self-sufficiency of fiction and she uses fiction to mask and disrupt the autobiographical impulse. Also in the 1970s she experiments with and parodies the themes and strategies of popular fiction. By means of these parodies Lispector casts an ironic light on her own practice elsewhere of finely wrought, introspective fictions of axivNTRODUCTIONkind that modernism had canonized as high art.

In the 1970s Lispector also questions most sharply the uncomfortable aggressions contained in the narrative pact. These include not only the age-old entanglement of narrative with the representation of suffering, but also the inward-turned and almost sacrificial suffering of the author that narrative may require. 'Can it be that it's my painful task to imagine in the flesh the truth that no one wants to face?' Lispector's narrator asks in A hora da estrela (1977; The Hour of the Star; HS 56). Lispector's text ensures that the writer's pain is shared by the reader.

A writing that insistently imagines disturbances of the psyche as well as painful transgressions of the social order and of the routines of fiction will necessarily be less than comfortable for the reader. The reader Lispector's fiction sometimes implies and at other times addresses must be startled, seduced, or even dominated in an uneasy engagement with her text. Some of the aggressive aspects of Lispector's narratives can be read as gendered, along the lines elaborated by feminist narratologists and film theorists (Laura Mulvey, Teresa de Lauretis, Tania Modleski). These critics have reflected on the relation of spectatorship to gender ideology and on the oppressiveness for women of a narrative based on 'a male Oedipal logic' (de Lauretis 1984, 152) that tends to exclude women from the position of subject. In another critique of the assimilation of the Oedipus model into cultural discourses, Jessica Benjamin discusses 'its updated, subtler form': 'a version of male dominion that works through the cultural ideal, the ideal of individuality and rationality that survives even the waning of paternal authority and the rise of more equitable family structures' (Benjamin 1988, 173). In her passionate fictions, Lispector undermines the authority of reason, which she repeatedly construes as a version of male domination, both in her characters and plots (or their erasure) and in the very texture of her dense, oxymoronic language with its tendency toward self-contradiction and the dissolution of logical sense.

Throughout her work, Lispector searches for alternate sources of power and organization. The intuitive and the improvisatory, which she associates with the feminine, replace rational construction and logical progression in the unfolding of her fictions; they also challenge the boundaries, separateness, and coherence of the subject. 'As if in a retort to the Cartesian dictum 'I think, therefore I am'., Lispector asks herself permanently 'I who narrate, who am I?' '(Nunes 1982, 21).

To answer this question in her fiction —or perhaps to avoid answers and persist in the questioning—author, narrator, and characters engage in vertiginous doublings and mirrorings. In one of her autobiographical pieces, she describes this exchange between self and other: Before, I had wanted to be other people to understand that which is not me. I then realized that I had already been others and that it was easy. MyINTRODUCTIONxvgreatest experience would be to be the inner core of others, and the inner core of others was me. (DW 508) In an earlier version of this fragment from A legido estrangeira (1964; The Foreign Legion), Lispector wrote 'the other of others' in place of 'the inner core of others,' pointing up the extent to which otherness inhabits the space of an inner core where identity and alterity become inextricably enmeshed.

'My greatest experience,' the earlier version reads, 'would be to be the other of others, and the other of others was me' (FL 119). A disunified, inconsistent subjectivity, unknown to itself, is constantly invading and being invaded by others, in a continuous exchange that forms and dissolves in the words of so many of her texts. This exchange between self and other at the heart of Lispector's fiction is not peaceful, but instead is charged with double-edged violent forces.

The passionate aspect of Lispector's writing, which many critics have noted and which Lispector herself stresses —in the title of A paixdo segundo G.H. (1964; The Passion according to G.H.), for example —involves not only the quest for positive connections, as in the passion of love, or the intense introspection of her characters, who seek contact with truths that reason cannot fathom or represent.

It also includes the sacrificial impulse that sparks her fictional imagination: a via crucis, with its Christian resonances of suffering in place of and for the sake of another, a process that does not always follow ethical and moral precepts, and that may be required of the characters as well as suffered by their author. In a closing autobiographical piece in The Foreign Legion, Lispector describes a strong, irrational response to the police shooting of the dangerous Brazilian outlaw Mineirinho, who 'had murdered far too often' (FL 213). He has infringed the commandment'Thou shalt not kill,' yet to her dismay she cannot accept the justice of his death: That commandment is my greatest guarantee: so do not kill me, for I do not wish to die, and do not let me kill, for to have killed would cast me into eternal darkness. This is the commandment. But while I listen to the first and the second shot with a sense of relief and reassurance, the third shot makes me alert, the fourth leaves me anxious, the fifth and sixth cover me with shame, I hear the seventh and eighth while my heart beats with horror, at the ninth and tenth my mouth is trembling, at the eleventh shot, I am appalled and invoke the name of God, and at the twelfth I call for my brother. The thirteenth shot kills me—because I am the other.

Because I want to be the other. (FL213) The meditation that follows probes the injustices of justice, the guilt for her own violence that she allowed him to carry for her, and the permeable boundaries between the virtuous and the sinful. In this book I argue that a similar vigilant alertness to inter- and intrasubjective violence shapes many of Lispector's narratives.xviINTRODUCTIONHere this alertness presented literally as the wrenching reversal from identification with the killer to identification with the victim, although the victim is a killer and his killers are the police. Her self-reflexive authors, especially in the later narratives, are uneasily aware of contradictory masochistic and sadistic investments in the fate of their characters. Lispector echoes their concerns in an interview of 1969, during which the interviewer reports: 'About her characters Lispector only says she is sorry she places them at times in terrible situations, but that is her way, a harsh way, inflexible, almost pitiless' (Gorga Filho 1969). My readings of Lispector's fiction point up the contradictory forces that strip her words of their power to shelter and, to their discomfort but also to their illumination, expose her readers to the storm. IIAs is often the case with modern Latin American writers, even long after their deaths, no book-length biography of Lispector exists.3 While living abroad, she wrote many letters to her sisters and Brazilian friends, who served informally as her literary agents.

Fragments from twenty-five of the letters to her sisters have been published (Borelli 1981), a small portion of what seems to have been an extensive correspondence. Lispector's talent was recognized immediately upon the publication of her first novel in 1944 (it won a literary prize and received many positive reviews), but only in the 1960s, when she returned permanently to Brazil after fifteen years in Europe and the United States, did she become celebrated in her country. That very celebrity, with its attendant proliferation of interviews (which she claimed to have hated and granted with at times obvious reluctance), complicates considerably the task of getting straight some basic facts about her life.

Lispector was sensitive about certain areas in her personal and literary life, and was not above lying when pressed for information about them. One area was her birth date and early childhood. She was generally believed to have been born in 1925, whereas documents that recently became public reveal her birth date as 1920.4 Lispector's reason for equivocating may well have been vanity, even literary vanity, in a wish to appear more precocious at the time of her literary debut in 1944. Her wish for privacy about this matter was preserved by her family: her tombstone does not register the date of her birth, only that of her death. (See photograph of Lispector's tombstone in Varin 1987, 220.) To help erase those years, Lispector stated many times that the family settled immediately in Recife, a major port in northeast Brazil, when they actually spent their three initial years in the smaller city of Maceio. Lispector's dating of events in her life, even her children's ages in her later years, is unreliable.

Her dating, however, does coincide with external evidence about two major events: her mother, a paralytic for allINTRODUCTIONxviiof Lispector's life, died when her daughter was nine, and at age twelve Lispector moved with her father and two older sisters to Rio de Janeiro. Lispector denied that she ever spoke or understood Russian, but in an interview with her eldest sister, Elisa Lispector, Claire Varin ascertained that Yiddish was spoken at home during Lispector's early years and that the child Clarice understood it even if she never spoke it. The many remaining questions about Lispector's early years, such as the family's economic circumstances (they were very poor, Lispector often said) and their participation, if any, in a community of Jewish immigrants, await answers in a much-needed biography.5 Elisa Lispector, also a novelist, has written an autobiographical novel, No exilio (1948; In Exile), which presents a version of those early years, shadowed by their mother's deteriorating health and death. This novel dwells on the family's story as an example of the Jewish diaspora and on the eldest daughter's difficult adaptation to Brazil.

It depicts a father passionately concerned with the fate of the Jews in Europe and with the establishment of Israel, and a family that retains Jewish customs. Another area of privacy for Lispector is her reading, especially when interviewers touch on literary influences and intellectual affiliations. Out of a fear of appearing merely derivative—early reviewers were quick to mention, much to Lispector's distress, the 'influences 'of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf—she almost always avoided questions about her literary interests, especially current ones, deflecting the issue back to her voracious and chaotic reading during adolescence.

At that time she was especially drawn to Dostoyevski, Katherine Mansfield, and Hermann Hesse; she also chose books from lending libraries alphabetically by the author ('So I got to Crime and Punishment rather quickly') or by the mere appeal of the title (Lowe 1979, 37). Although at times Lispector contradicts herself, she always claims to have read the writer in question only after writing the book he or she supposedly influenced. In an interview in 1979, for instance, she places her reading of Sartre in 1944 (Colasanti et al. 1988, 300); in another, she insists she had never read or even heard of Sartre until after she had written A mac.a no escuro (1961; An Apple in the Dark) (Lapouge and Pisa 1977, 197). Her wish apparently was to appear as a writer guided only by a dazzling intuition, but she clearly was not, as Olga Borelli (a close friend and author of a memoir about Lispector) has described her, simply 'a housewife who wrote novels and short stories' (Borelli 1981, 14). Letters to her sisters during her sixteen years abroad show her preoccupied with methodical reading and sustained, disciplined writing, and often distressed at falling short of her goals.

(Excerpts from those letters appear in Borelli 1981, 105-46.) 'I haven't written a single line,' Lispector complains in a letter of 1946 to one of her sisters, 'and this makes me very uneasy. I am always waiting for inspiration with an eagerness that leaves me no peace. I have even come to the conclusion that writing is what I most desire in the world, even more than love' (Borelli 1981, 114).xviiiINTRODUCTIONWhile attending law school, Lispector worked as a journalist in Rio.

In 1943, she married a fellow student who became a diplomat, with whom she lived abroad for the better part of the next fifteen years. In 1959, Lispector returned to Brazil with her two sons, after separating from her husband. She lived comfortably in an apartment facing Leme beach in Rio, supplementing her husband's financial support with income from translations and journalism, including a conventional biweekly women's column written under the pseudonym 'Helen Palmer' (tips on fashion, grooming, child rearing, makeup, recipes, advice on keeping a husband interested, warnings to refrain from appearing afemme savante.6 Lispector had friends who were important writers (Fernando Sabino, Rubem Braga, Nelida Pinon, among others), but she did not engage in anything that could be called a literary life. She insisted in almost every interview from the 1960s and 1970s that she was neither an intellectual nor a professional writer (by this she meant that she never kept to a schedule, but wrote only when she felt moved to do so). In 1967, she had to undergo several operations for the serious burns she suffered from a fire in her apartment that almost took her life. Her right hand, although not entirely incapacitated, became permanently impaired.

In the last decade of her life she was plagued by despondent moods that, from the evidence of her interviews, were at times acute.7 She continued to publish until her death from cancer on December 9, 1977, the day before her fifty-seventh birthday. IllAlthough Lispector was acclaimed early on as an extraordinary writer, it was not until more than twenty years after the publication of her first novel that a booklength study of her work appeared in Brazil.

In that book, Benedito Nunes's erudite and acute readings pointed up the philosophical issues in her work and were instrumental in securing for Lispector a respected position in the canon of Brazilian literature (Nunes 1966). As other critics were to do later, he traced the affinities between the philosophical ideas present in her fiction and those of Heidegger, Kierkegaard, Camus, and Sartre. Other of her early critics analyzed aspects of her style: her use of the epiphany and of rhetorical devices like the internal monologue. More recently, questions of gender, narrative, poststructuralism, and postmodernism have been brought to bear on her text. (See, for instance, Fitz 1987 and 1988b.) Lispector was singled out as one of two Brazilian writers (the other was Guimaraes Rosa) belonging to the so-called Boom of Latin American fiction in the 1960s. However, only in the late 1970s and 1980s did she emerge as an object of extensive international attention in the wake of feminist criticism and, perhaps especially, of Helene Cixous's celebration of her work as a model of ecriture feminine.INTRODUCTIONxixAlthough ten of Lispector's fourteen books of fiction are currently available in English, criticism of her work in English is still scarce.

In addition to a rapidly growing number of articles, there are two books: Earl Fitz's Clarice Lispector (1985), an overview of her complete fiction, and Helene Cixous's transcripts of her seminars on several of Lispector's texts entitled Reading with Clarice Lispector (1990). I will consider representative moments of Lispector's fiction in the following chapters, which are intended primarily as readings of certain texts, a task that is not superfluous in the case of a complex writer whose interpretation is far from exhausted. I hope as well that the paradigms I propose will prove applicable to other of Lispector's works and suggestive in the study of other women writers. My impetus for writing this book derives in part from my responses to other critics of Lispector, mainly from my objections to Helene Cixous.

Some of the information that guided my readings is new to Lispector criticism and was acquired in archival research in Brazil (unpublished letters, personal documents, early drafts of her work, and other papers from Lispector's private files recently made available for consultation). As I map shifting intersections of gender, narrative, and violence in Lispector's career, I arrange the texts I consider in roughly chronological order. Chapter 1 juxtaposes Lispector's first novel, Near to the Wild Heart (1944), and the short story 'The Misfortunes of Sofia' (1964), read as fictional portrayals of the developing artist and as meditations on gender and the female writer's vocation. In her presentation of writing as a gendered and violently disquieting enterprise, Lispector comes to a different conclusion in each text on how to bring about the vexed articulation of woman and writing. Whereas the novel describes artistic creation as requiring the ruthless (and joyful) refusal of gendered social roles, the short story shows the young girl discovering that female gender conveys a form of power that can be played to a writer's advantage.

In chapter 2,1 examine other instances of the conflict-ridden intersection of gender and development that have a less triumphant outcome. The plots of the short stories of Lagos de familia (1960; Family Ties) reveal the plight of women caught in gender roles, whereas the narrative strategies manipulate the reader alternately into sympathy and disdain for them. Chapter 3 addresses, in somewhat polemic terms, Cixous's influential readings of Lispector from the perspective, not of Lispector's usefulness to Cixous's own theoretical enterprise, as many of her American and European commentators have done, but of Cixous's illumination of Lispector's texts.

This reverse direction might seem unwarranted because Cixous is not a conventional critic 'at the service' of another author. It is, however, this very appropriation of Lispector, within a rhetoric that celebrates and imitates Lispector's nurturing, nonappropriative gaze, that I wish to point to and question.xxINTRODUCTIONChapter 4 studies two late works that mark a turning point in Lispector's writing: Agua viva (1973; The Stream of Life) and A via crucis do corpo (1974; The Stations of the Body). The conflictive tensions that earlier were located in her characters' actions and inner lives now also appear in the narrator's questioning of the very fiction she produces. At issue especially are the particularities of a woman's writing: its access to special modes of power, its obligation to uphold icons of femininity such as the nurturing mother, or its freedom to transgress the boundaries of conventional feminine decorum and of genre, especially those that distinguish autobiography from fiction and carefully crafted 'artistic' fiction from the more commercially appealing narratives that capitalize on sex and violence.

The concluding chapter was in many ways the point of departure for this book. In studying The Hour of the Star (1977), the last text Lispector published before she died, I became aware that it functioned not simply as a work of 'social criticism,' but rather as a radical questioning of how narrative itself was implicated in structures of domination and victimization. I attempt in this chapter to show a progression in Lispector's work from earlier stories, in which violence against women inheres in social, ideological, and aesthetic structures that somehow minimize and contain it, to a later stage that reveals how the violence inflicted on a particularly forsaken and comically helpless young woman springs from multiple sources. Lispector's broader vision brings out sharply these sources of violence in a way that does not spare either writer or reader. Although I have chosen for analysis texts in which the questioning of gender, narrative, and violence is explicit, others, such as The Passion according to G.H.

De Corpo Inteiro Clarice Lispector Pdf Online

Or the posthumous A Breath of Life would, I think, respond to investigations along similar lines. The chapters in this book are not intended, then, as a closed and fixed series, but instead as an opening up of areas of conflict in Lispector's work that have not been sufficiently addressed before. Neither do I want to substitute a 'violent' Lispector for the more accepted 'philosophical' or 'nurturing' one, but rather to bring up for discussion neglected aspects of her texts that are crucial to one of Lispector's main innovations: an inscription of the feminine that is not a sentimental withdrawal from the struggles of power, but is instead an exacerbated sensitivity to their workings and to women's—and writers' — involvement in these struggles, not as passive victims but as active participants. This study calls for a renewed attention to the letter of Lispector's text, to its densities and contradictions, to its tendency toward the ideologically and aesthetically transgress!ve, to its skill with comic, parodic, and farcical modes.